The rise of Alfons de Borja to the papal throne, under the name of Callixtus III, was, in many ways, an unexpected event. Nevertheless, it was a happening of great significance for Christendom’ struggle against the notorious Ottoman threat. The man who achieved the highest dignity on Earth, thus fulfilling the legendary prophecy of Vincent Ferrer, astonished his contemporaries with extraordinary agility and zeal.

Shortly after his election, Callixtus wrote an intense letter to the Christian rulers:

I, Pope Callixtus, vow to Almighty God and the Holy Trinity that by war, maledictions, interdicts, excommunications, and all other means in my power, even sacrifice my life if need be, I will pursue the Turks, the most cruel foes of the Christian name, to conquer again Constantinople, which has been captured and destroyed by Mehmet II in punishment for our sins, for the release of Christians who lie in slavery to strengthen the true faith.

This was not an ordinary document, but an oath and a resolute statement of a pontiff who took upon himself this historic mission.

The very first moments that followed his election as Pope, Callixtus abandoned the artistic projects of his predecessor, Nicholas V. Predictably, his attitude has drawn criticism from humanists at the papal court; but financial necessities of the anticipated crusade radically changed the budget priorities.

The main thought of the new Pope was saving Europe from heathen invaders. On May 15, 1455, he published the bull of the upcoming crusade, setting March 1, 1456 as the start date for the anti-Ottoman holy war. By this bull, the Pope enabled the taxation for financing the building of a powerful fleet and provided indulgences to all those who will support the military campaign.

During this period, the Supreme Pontiff ordered, for himself and for the Curia, a set of austerity measures without precedent. Jewelry, works of art and valuables held by the papal treasury, lands and properties owned by the Vatican, were auctioned and eventually sold. Any income was desirable in order to subsidize the ambitious anti-Turkish expedition.

In September 1455, the official messengers of Rome went to the proper channels to preach and obtain, from some specific European countries, money for the crusade. Prestigious clerics, including Alan de Coëtivy, Juan Carvajal and Nicholas of Cusa, were responsible, as papal representatives, in France, Germany and England. At first, the persuasive men of the Church were able to obtain important sums from some benefactors. It looked like a warlike endeavor against the Ottomans was going to be endorsed both financially and politically.

The war preparations intensified. A commission including illustrious cardinals such as Ludovico Trevisan, Pietro Barbo, Capranica, Latino Orsini, Bessarion and Guillaume d’Estouteville was tasked by the Pope to oversee the establishing of the upcoming papal fleet. An incident whose main character was the archbishop of Tarragona, Pedro de Urrea, was the first breach in Callixtus’ strategy. Urrea was appointed by the Head of the Catholic Church at the helm of some vessels that were supposed to attack the Ottoman naval army in the Aegean. Contrary to its mission, the archbishop of Tarragona took part, along with Alfonso, King of Naples, at a surprise offensive against Genoa. This infamous betrayal worsened the relations between Borja, now Bishop of Rome, and the Aragonese monarch and it brought them to a different level. On December 17, 1455, the Vicar of Christ assigned the effective leadership of the fleet to Ludovico Trevisan, the Warrior Cardinal, also the new papal legate in Sicily and the Greek islands.

Pope’s optimism and the capacity of his court to thoroughly prepare such a major campaign were two very different things. The initial date for depart, set nine months earlier, had to be postponed. This delay did not diminish the Callixtus’ confidence. Three months later, on May 31, 1456, Admiral Trevisan leaved Rome towards Ostia, leading a fleet of twenty-seven galleys. Papal naval army included 1,000 sailors and 5,000 soldiers. As planned, fifteen additional ships, promised by Alfonso of Naples, would have had to join the pontifical fleet.

In the Eternal City, the expectations were higher. By a new papal bull, at the end of June, the Catholic clergy spoke in sermons about the Ottoman vast danger to Christian world. Contrary to what Pope might have expected, the vessels promised by Alfonso were not made available to Admiral Trevisan and the fleet’s prolonged stand in the Kingdom of Naples has exceedingly complicated the current situation. The pontiff’s outrage was fully justified. In a letter addressed to Alfonso, Callixtus openly accused him of treason and threatened with a severe Divine punishment: “God and the Holy See will bring retribution down on you! Alfonso, aid Pope Callixtus, because if you do not, God will surely punish you!”

This behavior was far from being singular. Charles VII of France had promised thirty warships, but, in the end, he decided not to use them in the anti-Ottoman campaign. The fate of Christendom depended on the cohesion and the good faith of those important rulers, but this did not function as it should in the summer of 1456. The Turkish threat was continuously growing and the European powers were rather preoccupied with mutual rivalries and petty political games.

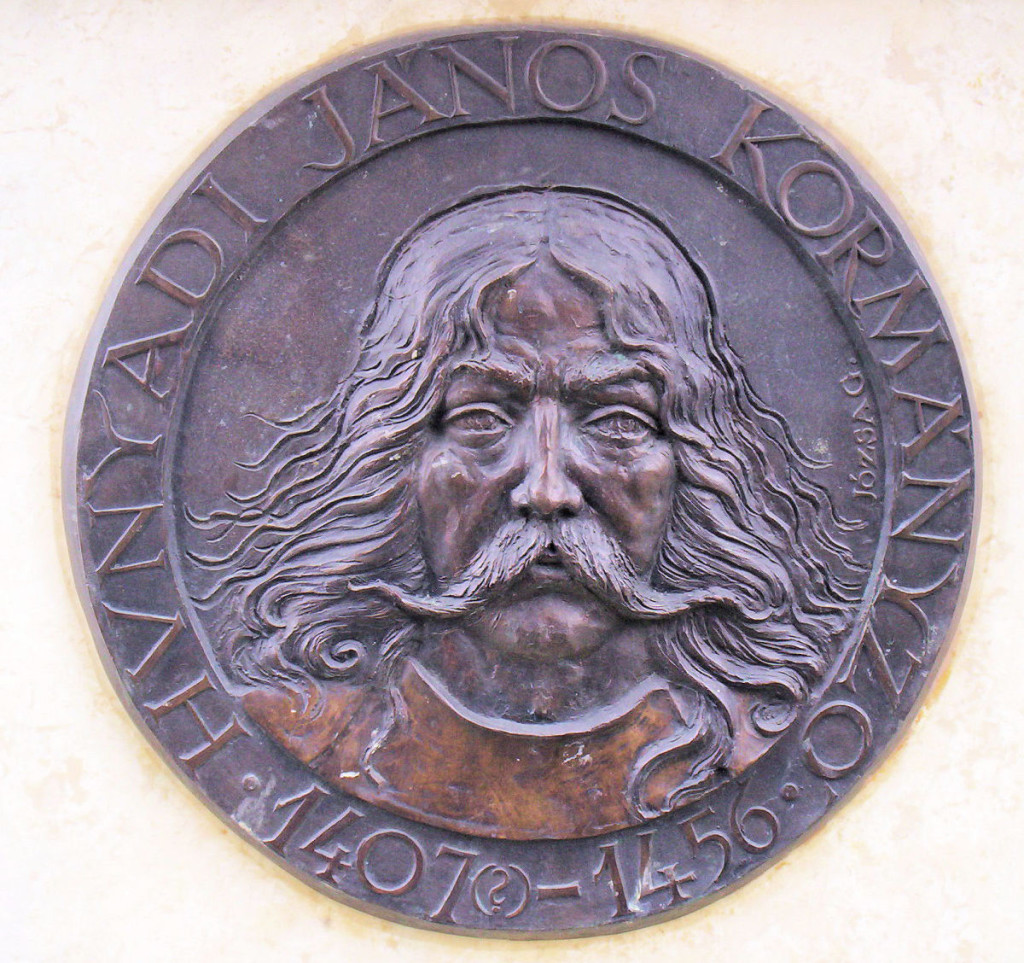

Although disappointing, these schemes and intrigues did not diminish hopes in Rome. Furthermore, the historical victory of John Hunyadi in defending Belgrade, in the July 1456, has brought tremendous joy at the papal court. On July 4, 1456, the hordes of Mehmet II the Conqueror began the conquest of Belgrade, the Serbian citadel highly significant, both symbolical and strategically. Few days later, the Ottomans suffered their first major defeat on the water, in the confrontation with the cruciate ships.

In his struggle to defend not only Hungary and the Eastern Europe, but the Christendom itself, the Transylvanian’ prince, John Hunyadi, was always been supported by two formidable men of the Church: Franciscan Giovanni Capistrano and Cardinal Juan Carvajal. Shortly after a series of bloody confrontations, following the counteroffensive launched by Hunyadi, on July 23 the sultan was forced to accept defeat and ordered his army withdrawal. The triumph of John Hunyadi, this brilliant strategist, was celebrated throughout Europe. At the Vatican, Callixtus invoked the power of God and extolled the hero of Belgrade, “the greatest man that the world has seen for three centuries”. The Vicar of Christ enacted that the Feast of Transfiguration to be celebrated annually, on August 6, the date the news of victory arrived in Rome.

The enthusiasm was short-lived, for the immediate deaths of Hunyadi (on August 11, 1456) and Giovanni Capistrano (on October 23, 1456) grieved once again the Christendom.

The Supreme Pontiff turned his attention to the German Empire, where the opposition to Frederick III had become increasingly aggressive. His concern was, of course, mostly financial. The holy war against the Turks needed on more and more cash. Callixtus continued to hope that he will convince the European leaders on the historical importance of their united action. But little did he succeed… Persuading the Germans was not an easy job. The demands were higher and things came to a deadlock.

This outcome was quite the same in other states, too. After the initial endorsement, most of European princes became rather indifferent to the zealous appeals from Rome. Nevertheless, the fleet led by Admiral Trevisan was miraculously active in the east of the Mediterranean Sea. Following the establishment of the base on the Rhodes Island, the crusaders managed to drive out the heathens and took over the city of Corinth. An extraordinary victory was the capture of twenty-five Turkish ships at Mytilene, in August 1457.

Although the events were encouraging, the needs were not properly met. Trevisan’ requests to supplement the troops and money were not fulfilled. Despite his efforts and ambition, the Bishop of Rome was isolated. He insisted one more time to Charles VII, but the French King delayed or simply ignored his demands.

This type of disregard was proven once again when the Pope tried to preside over a general congress to be held in Rome, in December 1457. Very few of the potential delegates answered to Callixtus’ desperate calls and, consequently, he was compelled to abandon this idea few months later.

Callixtus III, the first Pope from the Borja family, died on August 6, 1458, the very day of the Feast of Transfiguration which he himself enacted two years before. He departed this life disappointed by the lack of solidarity among the European rulers, who did not share his zeal to annihilate the Ottoman danger. He pursued this goal with sincerity and almost unique devotion. In those eighteen months spent at sea, the pontifical fleet obtained wonderful victories. Although very old and with poor health, Callixtus III never gave up to stand out against the expansion of the Ottoman Empire in Europe. Unfortunately, he is remembered less for his perseverance to the cause, but as the Catalan Pope who facilitated the ascension of his Spanish relatives in the Catholic hierarchy.